In the autumn of 2023, I began writing my text about nautical charts. I started but never finished, yet the preface turned out beautiful:

“Autumn. Crews hoist their vessels (and themselves) out of the water, yachts roll into ellings, canopies are hung over the decks, and there’s constant bustle near the slips.

When the piers empty, it becomes sad. This means that in addition to all the winter difficulties such as cold, eternal night, and walking challenges, another one will be added — sea hunger.

To solve this problem, two things were invented: icebreakers and buoys. But I haven’t tried either yet, so now, before the first ice, is the perfect time to go from land to water and talk about nautical charts.”

It’s already February now, and I haven’t sailed on an icebreaker or a buoy. But crews are busy repairing their boats, yacht clubs are more frequently bathed in sunlight, and I am once again inspired by all this and continue to write about maps.

You can go for a walk on the sea or along the rivers of St. Petersburg perfectly well without nautical charts if you know where the shallows are or, for example, that “something lies at the bottom near the thirteenth buoy.” We safely reached Kronstadt without detailed nautical charts, but even on such a small trip, it was very useful to check the depths or plan a route on professional charts. And if you’re sailing to a place you’ve never been before — please, be generous with navigation.

I’ll tell you why nautical charts are so different from land ones. Spoiler: sailors have something to envy.

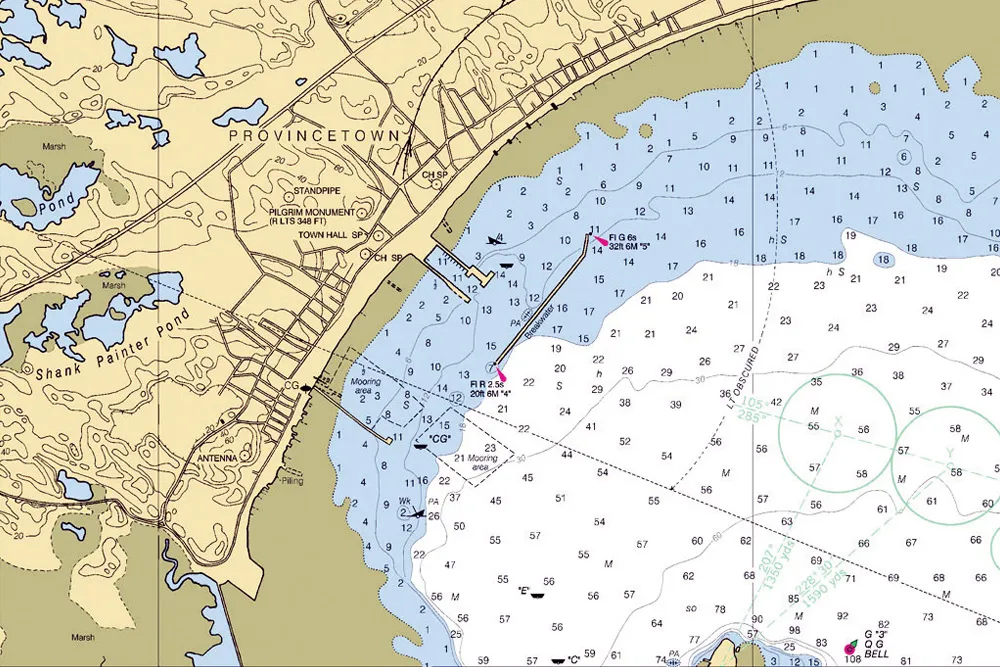

Fact 1. There’s a lot to sea 👁

If you look at land maps, the water in them is mega boring — a gigantic blue field. If you go out to sea and look around, it’s almost the same. A few ships, and around — the blue.

But there are quite a few navigational moments hidden in this blue, especially near the coastline. Here are a few quite ordinary objects that it’s useful to show on a map:

- Coastline, depths, and elevations: underwater and on land

- Landmarks on the coast: cities, ports, tall buildings, and chimneys

- Buoys and lighthouses marking routes or hazards

- Shipwrecks and underwater cables

Not so obvious, but also important:

- Various zones: places for anchorage, fishing, demagnetization, military tests

- Soil type (useful for anchoring)

- Bearings to noticeable objects

If the chart is electronic, let’s not forget to show on it all the plus-minus large vessels. This, by the way, is publicly available information. Look at MarineTraffic.

So, there’s a lot to show on the map.

Fact 2. Nautical charts are a bit ugly

And often sluggish too. This is, of course, explained by the amount of important information on them.

In nautical charts, there are numbers everywhere, hundreds of bathymetric lines, each buoy is drawn, and for lighthouses, there are also designations that tell sailors what color and frequency they shine.

Against the background of nautical charts, Yandex or Apple obviously win in visuals. But the detail of nautical charts is dictated by the conditions: when you’re at the helm, there’s no time to scroll the map and click on objects to find out some info. Everything should be visible.

Fact 3. Nautical charts are not free

We’re used to having Yandex.Maps, Google Maps, Apple Maps, or 2GIS installed on our phones. Not installed? No problem, just download.

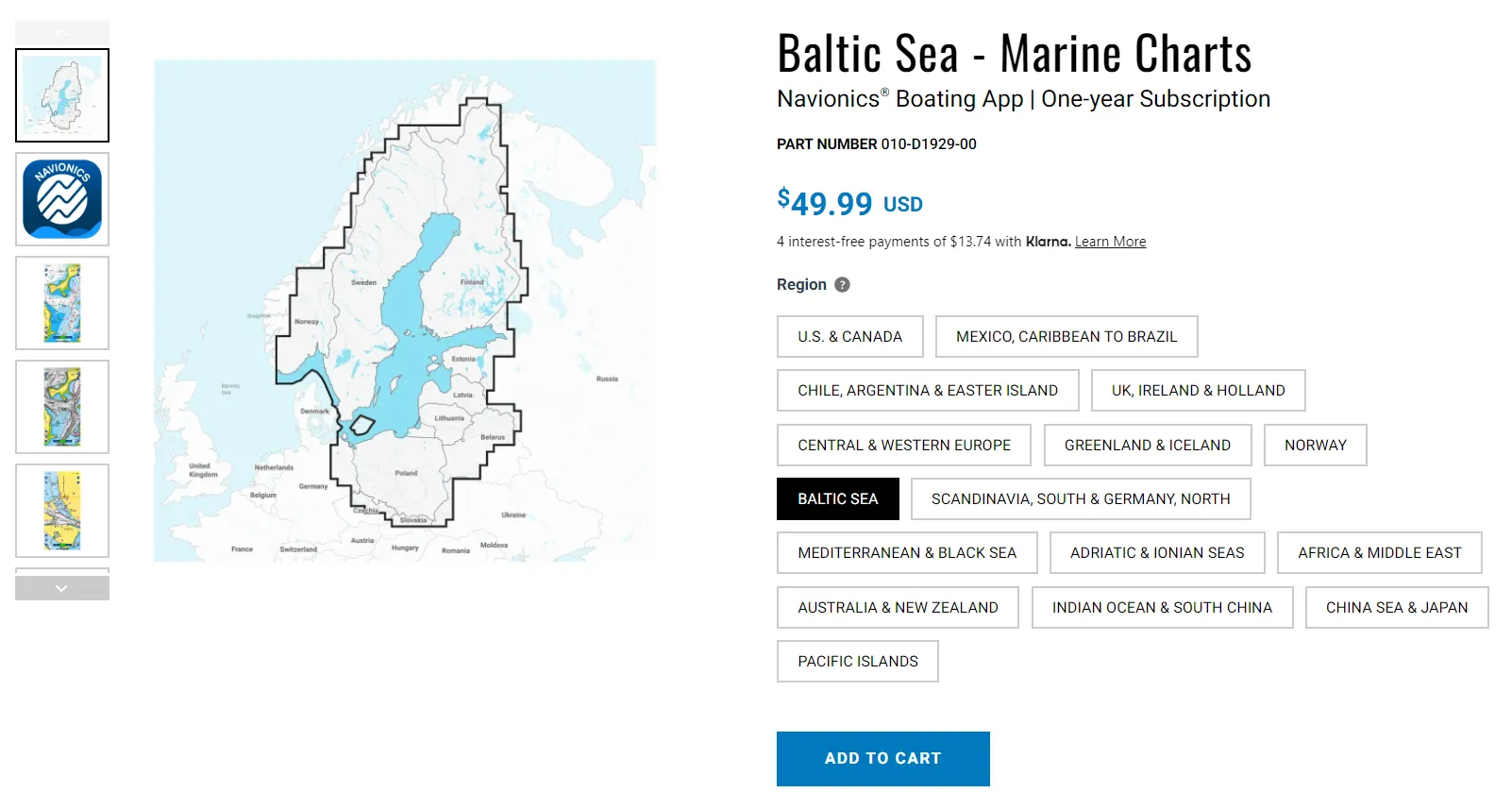

There are no such major providers for nautical charts like Yandex and Google, of course. The most famous brand, Navionics, belongs to Garmin. These are the guys who know navigation better than anyone and produce navigators and smartwatches.

Previously, fresh nautical charts were purchased from merchants, but now current information is also mostly sold for money. The most expensive are those with accurate depth markings. No one wants to run aground.

If you want to sail on the Baltic Sea, a mobile chart from Navionics will cost $50 (5,000 rubles). If you want to purchase a chart for a navigation chartplotter, it will cost 160–350 euros (16–35 thousand rubles). They’ll send it straight to you with a flash drive.

Free charts

If you need charts now and for free, there are solutions too. First — trial versions of the same Navionics or C-MAP. It won’t last long, but it’s quite easy to get a trial for the first time, and the charts are very detailed. Second — free services like OpenSeaMap and i-Boating.

OpenSeaMap is completely free, community members can add various signs, buoys, and routes to the map, but there are no depth marks at all. It’s convenient to turn on a nautical chart on your phone in the OsmAnd app (Android, iOS), and you can also view it on the web.

In i-Boating, there’s already a lot of information, and there are depth marks. But for the Baltic Sea, depths in many places are questionable. Trust your experience and colleagues. You can download the app on your phone (Android, iOS) and download one region for free. There’s a web version.

Fact 4. Maps are needed offline

In many apps, you can still download a specific city or area for free to use maps offline. When surrounded by 4G or 5G, this isn’t so important. But if there’s no internet where you are — it becomes necessary.

Far from shore, the internet is bad, so in long trips, offline maps are essential. That’s why map providers offer to buy a specific region, download it, and use it.

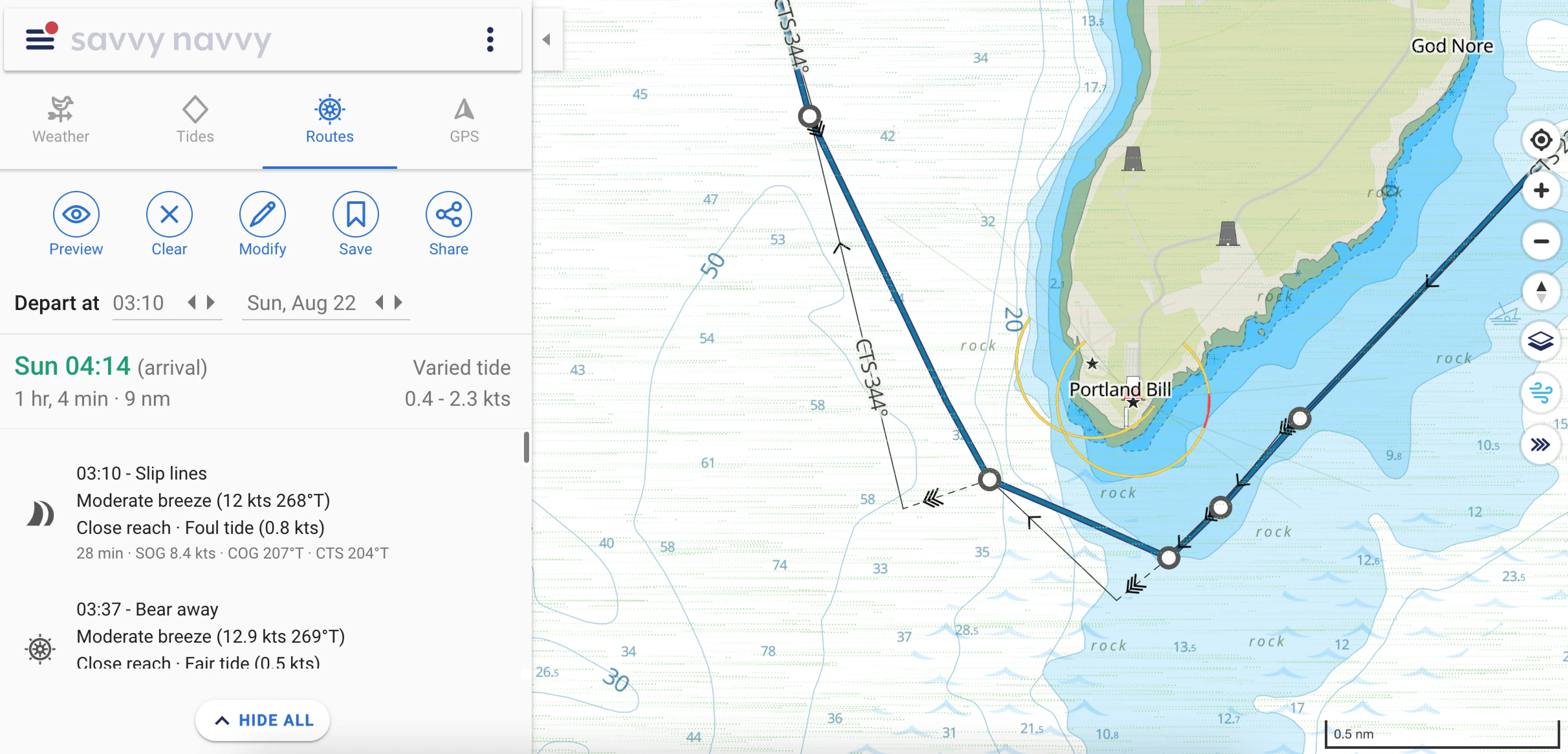

Fact 5. The route isn’t calculated automatically

On land maps, we usually press “here,” and the app calculates optimal routes based on algorithms: walking, driving, bus. At sea, routes are usually plotted manually. They try to make them as straight as possible because a straight line is the shortest path between two points.

Markers are placed to get onto the right course, bypass a cape, or pass at an adequate depth.

Since 2019, Navionics has been offering autonomous route planning (autorouting). The function is quite useful, but you can’t rely entirely on it like on a navigator in the city — you need to know the waters to avoid trouble.

Fact 6. Paper is needed

When you’re at sea, you have to think not only about how to get from A to B but also about how to survive and not ruin the boat. That’s why questions of safety and having a backup plan are damn important.

Electronic devices that don’t get wet, light up at night, and tell you about all the boats around — are a great thing. But power can go out on board, and instruments can fail.

That’s why it’s highly recommended to have a paper chart with a plotted route on the captain’s table. And every captain should know how to handle this paper chart.

If you want to try what it’s like to use nautical charts, download i-Boating (Android, iOS, web), look for familiar places, check out Monaco and St. Tropez, and plan a route across the Mediterranean Sea. This experience will surpass my article — you’ll understand everything at once.

If nautical charts have captivated you and you want to look at various charts in more